Environmental art is more than just art in nature; it's a creative conversation with the planet. Forget the traditional canvas and pristine gallery walls. For these artists, the world itself—the soil, rocks, water, and entire landscapes—becomes both their medium and their message.

The result is art that feels deeply rooted in its surroundings, speaking a language of place and time.

What Is Environmental Art Really About?

At its heart, environmental art is a movement that breaks free from the indoors and steps right out into the wild. The goal isn't just to make something beautiful, though it often is. It's about making us think and feel differently about our own place in the natural world.

The art itself is incredibly diverse. It can be as monumental as a massive sculpture that shifts and changes with the seasons, or as quiet and subtle as a piece designed to spotlight a pressing ecological issue.

Ultimately, this art form challenges that old idea of a hard line between humanity and nature. It invites us to see the landscape not just as a pretty backdrop, but as an active partner in the creative process. It's a perspective that nudges us toward a deeper, more thoughtful connection with our environment.

The Core Idea: A Bridge Between Art and Nature

The single most important principle of environmental art is site-specificity. This simply means a piece is designed for one particular location, and its meaning is completely tied to that place. A sculpture made from desert rocks would lose all its context and power if you moved it into a city museum.

The environment isn't just a stage; it provides the materials, the setting, and often, the entire idea behind the work itself.

This screenshot from Wikipedia gives you a glimpse into the sheer breadth of what falls under the environmental art umbrella, from huge land interventions to smaller, ecologically-focused projects.

As the image shows, artists are using natural materials and whole landscapes to create striking experiences that you just couldn't replicate indoors. That direct interaction is the very soul of the movement.

To quickly break down the key characteristics, this table gives you an at-a-glance understanding of what defines environmental art.

The Core Components of Environmental Art

| Characteristic | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Specific | The artwork is created for a specific location and its meaning is tied to that environment. | Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty, which is inseparable from the Great Salt Lake. |

| Natural Materials | Artists often use materials found on-site, like soil, leaves, stones, or water. | Andy Goldsworthy's sculptures made from ice, leaves, and balanced rocks. |

| Connection to Nature | The work explores themes of ecology, human impact, and our relationship with the planet. | Agnes Denes' Wheatfield, a piece that contrasted a field of wheat with Wall Street. |

| Often Ephemeral | Many pieces are designed to change over time, decaying or being reclaimed by nature. | A sculpture made of woven branches that biodegrades back into the forest floor. |

This table highlights how the art form is defined not just by what it looks like, but by where it is, what it's made of, and the ideas it sparks.

More Than Just a Pretty Picture

Ultimately, environmental art aims to do more than just decorate a landscape. It serves several powerful functions that make it a uniquely compelling art form. The primary goals often include:

- Raising Awareness: Many works grab our attention, shining a light on environmental problems like pollution, deforestation, or climate change. They make abstract issues feel tangible and personal.

- Fostering Connection: By creating art that invites you to walk through it, touch it, or watch it over time, artists forge a stronger emotional link between people and the natural world.

- Promoting Restoration: Some projects, often called "eco-art," are designed to actively heal damaged ecosystems, like by restoring wetlands or reintroducing native plants.

Environmental art is not just placed in the landscape; it is of the landscape. It uses the language of nature—growth, decay, erosion, and time—to tell stories about our relationship with the planet.

This approach makes the art feel alive. A piece might look completely different in the morning light than it does at sunset, or it could be transformed by a blanket of winter snow. This constant evolution is a key part of the experience, reminding us that both art and nature are living, breathing things.

Tracing the Ancient Roots of Environmental Art

https://www.youtube.com/embed/VXbliI5P89Y

While we think of "environmental art" as a modern movement, the impulse behind it is as old as humanity. It didn't just pop up out of nowhere. It's really the latest chapter in the long, winding story of how we relate to the natural world through art. To get what environmental art is all about, we have to go way back to the very beginning.

Our journey starts deep inside prehistoric caves. Tens of thousands of years ago, our ancestors were using charcoal from their fires and pigments from iron-rich earth to paint the world they saw around them. These weren't just doodles of animals on a rock wall. They were powerful acts of connection—a way to understand, influence, and maybe even honor the forces of nature that shaped every part of their lives.

This is the first time we see humans using the environment not just as a subject for art, but as the very stuff of art itself. This simple, profound act of creating with nature is the seed from which everything else in environmental art has grown.

From Painting Landscapes to Working With Them

For a very long time, artists mostly engaged with nature by painting pictures of it. The grand tradition of landscape painting is a perfect example. Artists got incredibly good at capturing the beauty, the drama, and the sheer power of the natural world on a canvas.

This hit a new level in the 19th century. You had artists like John Constable who became almost scientific in his obsession with painting clouds accurately. Then came the Impressionists, like Claude Monet, who spent his life chasing the fleeting effects of light on water lilies and haystacks. They weren't just painting pretty scenes; they were trying to bottle a specific, momentary experience of being in that environment.

These painters really pushed the boundaries of how we see and feel the landscape. They made nature an active, dynamic character in their art, not just a static background. This deep observation and respect for the natural world laid all the groundwork for the next big leap.

The Big Shift in Perspective

The 20th century is when things got really interesting. Building on this rich history, artists started asking a totally new question: "What if we stop just painting the landscape and start working in it?" This simple but game-changing idea shifted everything.

Instead of taking a canvas out into a field, artists began to see the field itself as the canvas. The environment went from being a passive subject to an active partner in the creative process. This is the moment art physically moved out of the gallery and started having a direct conversation with the wind, the rain, and the earth.

This transition marks the true birth of modern environmental art. It's where the line between the artwork and its setting starts to blur, creating a powerful experience where the art and the land are one and the same.

You can trace this creative line all the way back. The conceptual roots are clear, starting with those early humans using natural pigments for cave paintings and carvings between 40,000 to 4,000 B.C. These ancient works, showing animals and the world around them, reveal our timeless fascination with our environment. It's been a long journey from then to now, but it shows how artists eventually came to embrace nature as both their medium and their collaborator.

How a Modern Art Movement Was Born

While you can trace the roots of nature-inspired art back to ancient cave paintings or Impressionist landscapes, the environmental art movement we know today didn't just evolve—it exploded onto the scene in the 1960s and 70s. This wasn't a gentle shift; it was a full-blown rebellion. A powerful new wave of environmental awareness was sweeping across society, and for many artists, the clean, white walls of a gallery suddenly felt confining and sterile.

They felt an urge to create something bigger, something wilder, and something that was truly connected to the planet. The traditional art world, with its focus on polished objects to be bought and sold, seemed completely out of sync with the urgent conversations about ecology and our impact on the Earth. So, artists started looking for a new canvas—one as vast and untamed as the landscape itself.

This impulse drove them out of the studio and into the deserts, lakes, and open plains of America. They weren't just looking for a change of scenery; they were creating a whole new artistic language, one that spoke in the raw dialect of stone, soil, and water.

A Jetty in a Salt Lake

If you had to pick one piece that captures this radical spirit, it would have to be Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. Created in April 1970, this monumental work instantly became an icon for what was then called Land Art or Earthworks. It was wildly ambitious, deliberately remote, and utterly inseparable from its home.

Smithson picked a strange, secluded spot on the northeastern shore of Utah's Great Salt Lake, a place famous for its otherworldly, reddish-pink water colored by algae and bacteria. With heavy earthmoving equipment, his team muscled over 6,000 tons of black basalt rock and earth into a massive spiral that coiled 1,500 feet out into the lake.

This was so much more than a sculpture. It was a living dialogue with nature. The Spiral Jetty became a prime example of this new movement, which solidified during this period of cultural awakening. By submerging and re-emerging with the lake's fluctuating water levels, it physically embodies nature's constant state of change. You can dive deeper into how this piece helped define the era and protest the commercial art world in this insightful article on the movement's history.

The Spiral Jetty was a declaration of independence. It proved that art could exist outside the market, be subject to the forces of nature, and demand a pilgrimage from its audience, transforming the act of viewing art into a genuine experience.

When the lake’s water is high, the jetty vanishes beneath the surface. When the waters recede, it reappears, caked in a brilliant white crust of salt crystals. Smithson embraced this unpredictability. For him, the artwork was never "finished"—it was constantly being remade by the very environment it called home.

Pioneering a New Frontier

Smithson wasn't out there alone. A whole group of artists was exploring this new frontier, creating groundbreaking works that completely redefined the relationship between art and the natural world.

- Nancy Holt's 'Sun Tunnels' (1973-76): Out in the Utah desert, Holt placed four huge concrete cylinders to perfectly frame the rising and setting sun on the summer and winter solstices. She drilled holes in the tunnels to align with constellations, brilliantly bringing the mind-boggling scale of the cosmos down to a human experience.

- Agnes Denes's 'Wheatfield A Confrontation' (1982): In a stunning act of protest, Denes planted and harvested two acres of wheat on a landfill in lower Manhattan, just a stone's throw from Wall Street. That golden field, set against the city's steel and glass, was a powerful statement that forced people to question their ideas about land, value, and global food systems.

These pioneering works all shared a certain audacity. They were bold, visionary, and woven through with a potent ecological or social message. Each piece went far beyond just looking good to ask some deep, and often uncomfortable, questions about our place in the world.

These artists weren't just making objects; they were creating destinations. They were choreographing experiences. Their work laid the foundation for everything environmental art would become, proving that the greatest gallery on Earth is the planet itself. They didn't just start a trend—they defined a vital new era of art that continues to challenge and inspire us today.

Exploring the Different Styles of Environmental Art

The term "environmental art" isn't a neat little box; it's more like a sprawling, ancient tree with many branches. Each branch represents a different way artists have tried to connect with, question, or even heal the natural world. Digging into these different styles helps you see just how rich and varied this art form truly is.

While every style shares a fundamental tie to nature, their goals and methods can be worlds apart. It’s a bit like the difference between a landscape photographer and a park ranger. One captures the beauty of the environment, while the other actively works to preserve it. The intention behind the work changes everything.

Let's walk through some of the most important branches of this movement. Getting a feel for these different approaches will give you a much deeper understanding of environmental art in all its forms.

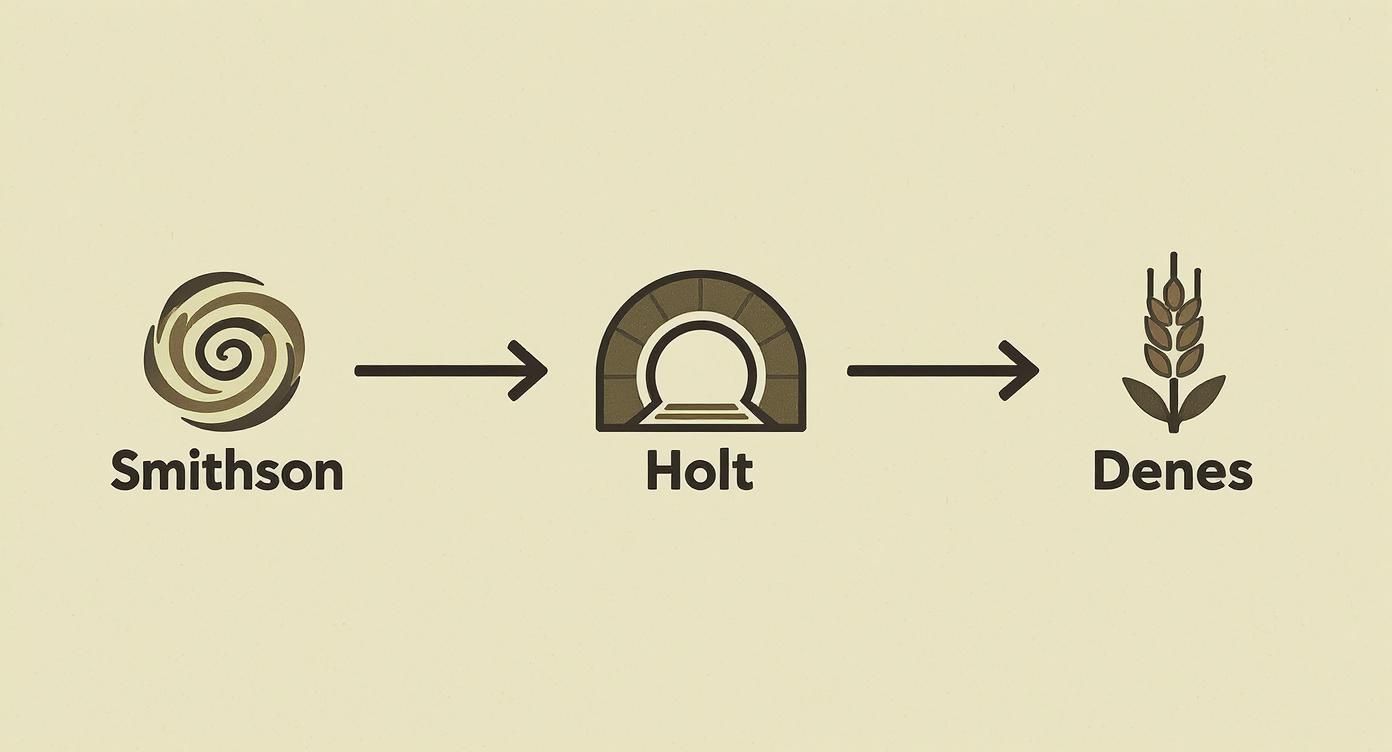

This infographic gives you a great visual starting point, highlighting some of the pioneers who forged these distinct paths.

You can see how foundational artists like Smithson, Holt, and Denes each claimed a different piece of the natural world—earth, sun, and agriculture—pushing the movement in exciting new directions right from the get-go.

Land Art and Earthworks

When people first hear "environmental art," this is usually what they picture. Land Art, also known as Earthworks, is all about going big. These are the ambitious, often massive sculptures built directly into the landscape using the earth itself as the primary material.

Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty is the poster child for this style. These pieces are almost always found in remote, wide-open spaces, making the journey to see them part of the experience. Land Art is focused on form, awe-inspiring scale, and the raw relationship between a human-made structure and the wildness of nature.

Ecological Art or Eco-Art

If Land Art is about reshaping the land, Ecological Art, or Eco-Art, is about healing it. This style isn't about making a grand sculptural statement. It’s about restoration, education, and getting the community involved. Eco-artists often team up with scientists, ecologists, and local residents to tackle real-world environmental problems.

An Eco-Art project might look like:

- Restoring a polluted wetland by bringing back native plants.

- Creating "living sculptures" that double as habitats for birds or insects.

- Designing artistic installations that actively filter contaminated water or soil.

The heart of Eco-Art is functional. It’s often a form of activism where the art isn't just something to look at; it's a process that tries to leave the environment better than it was found. This is what’s known as regenerative practice.

This approach is all about interconnectedness, turning art into a powerful tool for positive ecological change.

Sustainable Art

A close cousin to Eco-Art, Sustainable Art zooms in on the materials and methods used to make the art. The whole point is to create something with the smallest environmental footprint imaginable. Artists in this space think deeply about the entire life cycle of their materials.

That means they prioritize resources that are:

- Renewable: Think bamboo, fast-growing grasses, or other materials that replenish quickly.

- Recycled or Upcycled: Giving trash a new life by transforming it into art.

- Biodegradable: Making temporary works from things like leaves, ice, or unfired clay that can disappear back into the earth without a trace.

Andy Goldsworthy is a master of this. His stunning, temporary sculptures are made from found natural objects and exist only for a moment before nature reclaims them. His work is a beautiful commentary on the cycles of growth and decay.

Where Does William Tucker Fit In?

So, where do the heavy, powerful sculptures of an artist like William Tucker land in all of this? Tucker carves out a really unique space for himself. His work isn't Land Art in the traditional sense—he’s not moving tons of earth—and it’s not an Eco-Art project designed to restore an ecosystem.

Instead, Tucker’s bronze and stone pieces start a deep conversation with their natural surroundings. His abstract shapes feel primal, almost geologic, as if they were dug up from the ground rather than placed on top of it. They force you to think about form, weight, and texture within a natural context.

By setting his work outdoors, Tucker makes us more aware of the environment around it. The way sunlight glints off a bronze surface, the slow crawl of a shadow across the grass, the stark contrast between a solid sculpture and the living trees—these interactions become part of the art. His work is a reminder that environmental art can also be about slowing down, looking closer, and finding a modern human connection to ancient, elemental forms.

The Evolution of Eco-Art Into Modern Activism

As the massive earthworks of the 1970s began to weather and settle into the landscape, the world of environmental art was quietly starting to change. That first incredible burst of energy was all about scale, presence, and escaping the sterile confines of the gallery. But as the decades passed, artists began to channel that energy in a new way. The focus shifted from awe-inspiring interventions in the land to pointed, urgent activism.

The conversation started to evolve. Artists went from asking, "What can we build in the landscape?" to "What can we say about our impact on it?"

This wasn't a random shift. It was a direct response to a growing global consciousness. The quiet hum of environmental concern from the 70s grew into a roar as issues like climate change, pollution, and staggering biodiversity loss became front-page news. Artists, who are often society's canaries in the coal mine, responded by creating work that was less about abstract forms and more about very real, very concrete problems.

The art itself became a tool for change. This new wave of "eco-art" emerged as a powerful voice for advocacy, education, and sometimes even direct action.

Art Meets Science and Data

One of the defining features of this modern evolution is the incredible way art has teamed up with science and technology. Contemporary environmental artists are rarely just sculptors or painters anymore. Many are part-time researchers and collaborators with scientists, using hard data as their artistic medium. Their goal? To make the invisible visible. They transform complex scientific information into compelling, emotional experiences that hit you right in the gut.

This data-driven approach has unlocked a whole new world of creativity, giving artists a fresh language to talk about modern challenges in a way that feels immediate and incredibly relevant.

A Case Study in Visibility: Particle Falls

Andrea Polli's project, Particle Falls, is a perfect example of this new direction. This isn't some static sculpture you walk past; it's a living, breathing visualization of the air we're breathing. Polli uses a scientific instrument called a nephelometer to measure particulate pollution in the air, in real-time.

She then projects that data as a mesmerizing waterfall of light onto the side of a building. When the air is clean, the light is a calm, beautiful blue. But as pollution levels spike—often from passing cars—the waterfall erupts in fiery bursts of orange and red.

Particle Falls is a brilliant piece of modern eco-art. It takes an abstract threat that we all know exists but can't see—air pollution—and makes it stunningly, unavoidably obvious. It’s more than just art; it’s a public service announcement, a scientific tool, and a conversation starter, all rolled into one.

Polli’s work perfectly captures the spirit of modern environmental art. It's interdisciplinary, it's technologically savvy, and it directly engages the public with an issue that impacts their health every single day.

Inspiring Action and Proposing Solutions

But today's environmental art often goes beyond just sounding the alarm. It actively proposes solutions and inspires people to take tangible action. In the spirit of walking the walk, many eco-artists make a point of using eco-friendly construction materials in their installations, ensuring the medium truly reflects the message.

You can see this proactive, solution-oriented spirit everywhere:

- Artists are creating floating islands from recycled plastics that actually help clean polluted rivers.

- Community-led projects are transforming neglected urban lots into vibrant gardens buzzing with biodiversity.

- Installations are being built to showcase innovative ways to generate sustainable energy or harvest rainwater.

This is what defines the cutting edge of the movement today—art that doesn't just point out a problem but actively tries to be part of the solution. To see more of this in practice, check out our guide on powerful environmental art examples that are making a real difference.

From its roots in land art to its current role as a form of powerful activism, the evolution of environmental art shows its incredible capacity to adapt, respond, and lead the conversation about our planet's future.

Why Environmental Art Is More Important Than Ever

In an age where we’re flooded with data and digital noise, it's easy to feel disconnected from the natural world. Environmental art slices through that static, grounding us in what’s real and tangible. Its power has grown because it speaks directly to our senses and emotions, forging a link between abstract threats and our own lives.

This isn't just about pretty landscapes. It's about fundamentally re-evaluating our relationship with the environment. Environmental art takes massive, often unseen problems—like climate change or pollution—and makes them personal and impossible to ignore.

Making the Invisible Unforgettable

Let's be honest: grasping the sheer scale of something like biodiversity loss or air pollution is tough. How do you feel a statistic? Environmental art’s real genius is its ability to translate these huge, faceless concepts into something you can experience firsthand.

Imagine an installation that visibly changes color as air quality shifts. Suddenly, invisible pollution becomes a palpable presence. Or think of a sculpture built from the wood of a locally endangered tree; it tells a story of loss far more powerfully than any chart or graph ever could. This is where environmental art shines.

Forging Deeper Personal Connections

More than just a warning sign, this art is an invitation. It encourages you to walk through a field, touch materials pulled from the earth, and interact with the landscape itself. It’s a powerful reminder that we aren't just observers of nature—we are part of it.

That deep-seated connection is crucial for inspiring a genuine desire to protect our environment. You can see this same idea gaining traction in other fields, like the growing interest in stone design trends in biophilic design, where the goal is to weave natural materials back into our daily lives and strengthen that bond.

Environmental art reminds us that the Earth is not just a resource to be used, but a living partner in a shared story. It shifts our perspective from consumption to collaboration, urging a more thoughtful and reciprocal relationship with our world.

Inspiring Hope for a Better Future

Perhaps its most vital role today is offering a sense of hope. This isn't just about pointing fingers at problems. Environmental art actively explores and models solutions, showing us that a more sustainable future is not only necessary but possible.

When an artist creates a piece that helps heal a scarred landscape or provides a new habitat for wildlife, they demonstrate that regeneration is within our reach.

These works become symbols of what we can achieve. They highlight the undeniable link between art and climate change and prove that creativity can be a driving force for real action. The artist becomes a storyteller, an activist, and an innovator all at once—a role that has never been more critical. When we seek out these pieces, we're doing more than just looking at art; we're joining a vital conversation about the future of our planet.

Got Questions? We’ve Got Answers

The world of environmental art is vast and fascinating, so it's only natural to have a few questions pop up. It’s a field with a lot of overlapping ideas and unique approaches. Let's clear up some of the most common queries.

Think of this as your friendly guide to the big ideas. We'll sort out the key terms, talk about how long these pieces last, and even point you toward seeing some of this incredible art for yourself.

What's the Difference Between Environmental Art and Land Art?

This is a great question, and it's all about scope. Think of Environmental Art as the big, overarching category—the main trunk of the tree, if you will.

Land Art, often called Earthworks, is a major branch on that tree. It's the term for those awe-inspiring, large-scale sculptures made directly in and from the landscape. Robert Smithson's Spiral Jetty is the classic example; it’s monumental, site-specific, and made of the earth itself.

But Environmental Art is so much more. It also includes:

- Eco-Art: Art that actively helps restore or heal a damaged environment.

- Activist Art: Pieces that serve as a direct protest against things like pollution or deforestation.

- Sustainable Art: Works created from found objects, recycled materials, or things that will naturally biodegrade.

So, here's the bottom line: all Land Art is environmental art, but not all environmental art is Land Art. The broader term covers everything from pure aesthetics to direct ecological action.

Is Environmental Art Meant to Last Forever?

Not at all! In fact, some of the most powerful works are designed to disappear. The concept of impermanence is a huge part of the movement. Artists like Andy Goldsworthy are famous for creating breathtaking sculptures from things like ice, leaves, and twigs, knowing full well they will melt, decay, or get washed away.

This fleeting nature is intentional. It's a direct commentary on the art world's traditional obsession with creating permanent, sellable objects. Instead, it reflects the natural cycles of growth and decay, reminding us that so much of life's beauty is temporary.

The artwork’s short life forces you to be in the moment and appreciate what’s right in front of you, just like watching a storm roll in or the seasons change.

How Can I See Environmental Art in Person?

Seeing this kind of art is often an adventure in itself. Because so many famous pieces are tied to a specific location, visiting them can feel like a pilgrimage, requiring a real journey out into the landscape.

But you don't always have to book a trip to the middle of nowhere. Amazing works can be found much closer to home. Here are a few places to start looking:

- Sculpture Parks: Many outdoor parks have incredible installations that blend right into the natural setting.

- Botanical Gardens: These are perfect spots for artworks, temporary or permanent, that interact with the surrounding plant life.

- Urban Public Spaces: Keep your eyes peeled in city parks and plazas for commissioned projects that tackle environmental themes.

And don't forget contemporary art museums. Many now feature exhibitions dedicated to environmental art and eco-activism, which is a fantastic way to see a wide range of styles all in one place.

At William Tucker Art, we're driven by the power of art to forge a deeper connection with the natural world. Our collections are a celebration of our planet’s beauty, from stunning wildlife portraits to evocative coastal scenes.

Explore the collections at William Tucker Art and bring a piece of nature’s story into your home.