Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper is more than just a painting; it's a cultural touchstone that has captivated audiences for over five centuries. But what happens when this iconic religious scene is filtered through the lens of pop culture, feminism, or contemporary politics? The result is a vibrant and provocative collection of last supper modern art that challenges our perceptions and breathes new life into a timeless story.

This article explores six groundbreaking reinterpretations, analyzing how each artist uses the familiar composition to start a new conversation. We'll break down the strategies, techniques, and cultural impact of these modern masterpieces, from Andy Warhol’s commercial commentary to Kehinde Wiley’s powerful statement on representation.

You will see exactly how these artists deconstructed and reassembled a classic to make it relevant today. We will delve into how these works not only pay homage to Leonardo but also use his framework to address the most pressing issues of our time. This list provides a fresh perspective on art's enduring power to provoke thought and reflect society, offering specific insights into the creative process behind each piece.

1. Andy Warhol's The Last Supper (1986)

It's impossible to discuss modern art reinterpretations of The Last Supper without starting with the king of Pop Art himself, Andy Warhol. Commissioned in 1986, this was Warhol's final major series before his death, and it's a monumental exploration of one of Western art's most sacred images through the lens of mass production and commercialism.

Warhol didn't just create one painting; he produced over 100 works on the theme. Using his signature silkscreen technique, he treated Da Vinci’s masterpiece like any other piece of pop culture iconography, similar to a Campbell's soup can or a portrait of Marilyn Monroe. This approach stripped the original of its singular "aura" and reproduced it endlessly, questioning ideas of authenticity and originality in art.

Analysis: Blurring Sacred and Profane

Warhol’s strategy was to overlay the sacred image with symbols of modern consumerism. In versions like The Last Supper (Dove), the logo for Dove soap is superimposed, creating a jarring yet thought-provoking connection between spiritual purity and a household cleaning product. Another piece incorporates the Camel cigarettes logo, linking a biblical scene with a brand known for its own powerful, mass-marketed identity.

Strategic Insight: By juxtaposing religious iconography with corporate logos, Warhol forces the viewer to confront how modern culture consumes and commercializes everything, even faith. He transforms a sacred moment into a repeatable, branded product.

This provocative fusion of high art and low culture is a hallmark of last supper modern art, demonstrating how contemporary artists challenge and recontextualize historical works.

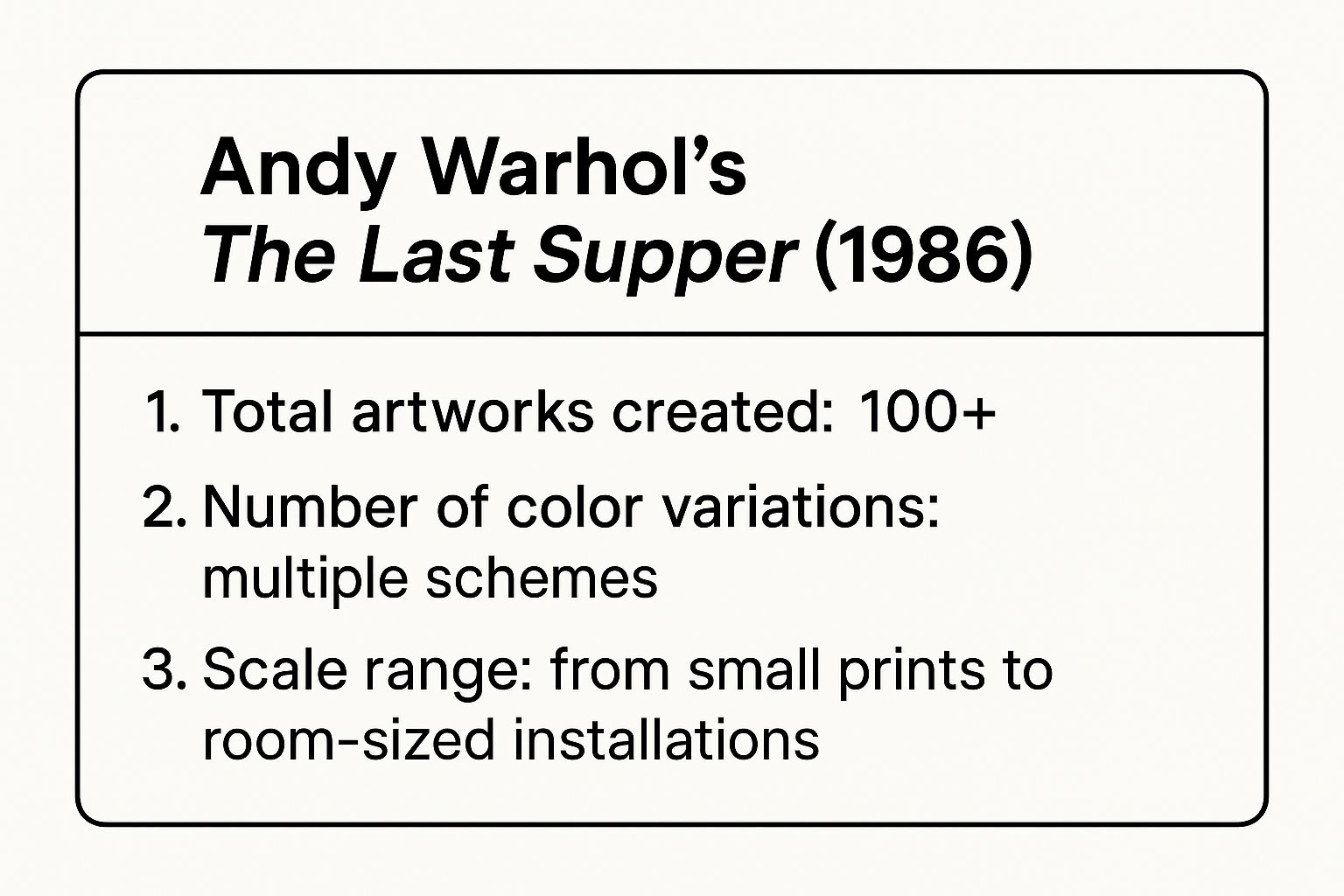

Key Data on Warhol's Series

To grasp the sheer scale of this project, here's a quick reference summarizing the key data points of Warhol's ambitious final series.

The infographic highlights the massive scope of the series, showing how Warhol used repetition and scale to amplify his commentary on mass media and consumer culture.

Actionable Takeaways

What can we learn from Warhol’s approach?

- Juxtapose Opposites: Combine seemingly unrelated elements (like the sacred and the commercial) to create new, surprising meanings. This forces your audience to see familiar images in a completely different light.

- Embrace Repetition: Don’t be afraid to repeat a core image or idea. Warhol shows that repetition can emphasize a theme, making a stronger statement than a single work ever could.

- Challenge Originality: Question the idea of a single, perfect masterpiece. By creating multiple versions, Warhol suggests that art's meaning can change with each new context, color scheme, or overlay.

2. Gerhard Richter's Abstract Last Supper Interpretations

Where Warhol used repetition to explore mass culture, German master Gerhard Richter takes a completely different path, using abstraction to delve into the spiritual and emotional core of Da Vinci's masterpiece. Richter's interpretations strip away the literal figures and narrative details, transforming the iconic scene into a ghostly, ephemeral experience that speaks to memory, faith, and the very act of seeing.

Using his famous squeegee technique, Richter drags and scrapes layers of paint across the canvas, blurring and obscuring the underlying composition. The result is a work that feels both familiar and unknowable. You can almost discern the shapes of Christ and the apostles, but they dissolve into pure color and form the moment you try to focus on them. This process reimagines a definitive historical moment as something fluid and deeply personal.

Analysis: Memory and the Spiritual Afterimage

Richter’s approach isn't about erasing the original but rather about revealing its "afterimage," the impression it leaves on our collective cultural memory. By blurring the figures, he removes the specific historical narrative and invites viewers to connect with the scene's raw emotional and spiritual essence: betrayal, divinity, and camaraderie. The paintings become a meditation on how we remember and process such powerful images over time.

Strategic Insight: Richter’s abstraction forces the viewer to move beyond simple recognition. By obscuring the literal image, he makes the act of looking an active search for meaning, mirroring a spiritual quest for faith in a world of uncertainty.

This powerful technique is a cornerstone of last supper modern art, showing how artists can use abstraction to explore profound religious themes without being confined by traditional representation. Richter’s work represents a fascinating intersection of styles. You can learn more about how artists blend these worlds in the captivating artistry of abstract realism.

Actionable Takeaways

How can we apply Richter's thoughtful approach?

- Focus on Essence, Not Detail: Instead of recreating an image perfectly, try to capture its emotional or spiritual core. Ask yourself what feeling the original work evokes and translate that feeling into color, texture, and form.

- Embrace Ambiguity: Don't give the viewer all the answers. By creating a blurred or abstract image, you encourage active participation and allow for multiple personal interpretations, making the work more engaging.

- Layer and Obscure: Use techniques like layering, scraping, or blurring to suggest history and memory. This creates a sense of depth and shows that the final image is built upon what came before, both literally and conceptually.

3. Susan Dorothea White's The First Supper (1988)

Australian artist Susan Dorothea White offers a radical and deeply personal re-envisioning of Leonardo's masterpiece with The First Supper. Painted in 1988, this work directly confronts centuries of patriarchal tradition in both religious and art history by replacing Jesus and his male apostles with thirteen contemporary women from diverse backgrounds, all gathered around a distinctly Australian table.

White's painting retains the compositional brilliance of the original but populates it with figures who represent a cross-section of female identity and achievement. The central Christ figure is an Aboriginal woman, a powerful statement on colonialism, spirituality, and the marginalization of Indigenous voices. This thoughtful recasting transforms the scene from a purely biblical narrative into a celebration of female solidarity and a critique of historical exclusion.

Analysis: Reclaiming the Narrative

The power of The First Supper lies in its direct subversion of traditional iconography. The setting is not a grand hall in Jerusalem but a simple, rustic Australian environment, complete with a Hills Hoist clothesline visible in the background. The food on the table is local and familiar, grounding the sacred scene in everyday reality. Each woman is an individual, not just a stand-in apostle, inviting viewers to question who gets a seat at the table of history.

Strategic Insight: By replacing every male figure with a woman and localizing the setting, White doesn’t just reinterpret the scene; she reclaims it. She argues that the spiritual and historical narrative has been incomplete, and she uses the familiar structure of a masterpiece to present a powerful, alternative history.

This piece is a cornerstone example of feminist last supper modern art, demonstrating how a classic work can become a canvas for social and political commentary.

Key Data on The First Supper

To understand the intentionality behind White's composition, it's helpful to see how she meticulously planned her subversion of the original.

The infographic details the artwork's dimensions and highlights the symbolic shift from a male-centric European setting to a diverse, female-led Australian one, underscoring its feminist and post-colonial themes.

Actionable Takeaways

What can we learn from White’s bold reinterpretation?

- Subvert Expectations: Take a well-known story, image, or concept and change its core components. Swapping genders, changing locations, or altering historical contexts can create a powerful new message.

- Ground the Universal in the Local: By placing a universal theme in a specific, local setting, you can make it more relatable and impactful. The Australian backdrop makes White's commentary feel immediate and personal.

- Champion Underrepresented Voices: Use your platform to give prominence to figures or groups who have been historically marginalized. White’s central placement of an Aboriginal woman is a deliberate act of re-centering the narrative.

4. Kehinde Wiley's The Last Supper (2009-Present)

Kehinde Wiley, renowned for his portraits of contemporary African American figures in heroic, classical poses, takes on Leonardo’s masterpiece with a powerful and disruptive vision. Instead of a single painting, Wiley’s interpretation is an ongoing series that recasts Christ and his apostles with young, Black men from Brooklyn, whom he encountered through his "street casting" process.

Set against his signature ornate, floral backgrounds, Wiley’s work directly confronts the historical exclusion of Black individuals from the canon of Western art. By placing these men into one of art history’s most revered scenes, he elevates them to a status of grace, power, and divinity traditionally reserved for white European subjects. The result is a stunning piece of last supper modern art that reclaims history.

Analysis: Reclaiming the Narrative

Wiley’s work is a masterclass in recontextualization. He preserves the dramatic composition and emotional tension of Leonardo's original, but every other element serves to challenge and subvert it. The subjects wear their own contemporary clothing- hoodies, jeans, and sneakers- which roots this sacred moment firmly in the 21st-century urban experience.

Strategic Insight: By replacing the historical figures with contemporary Black men, Wiley doesn't just insert them into the narrative; he demands that the viewer recognize their inherent dignity and question why they were ever excluded in the first place.

This act of substitution is a political statement. It critiques the power structures that have historically defined who gets to be seen as divine, important, or even fully human in Western culture.

Key Data on Wiley's Approach

To understand the core of Wiley's method, consider these key elements that define his powerful reinterpretations.

- Street Casting: Wiley scouts his models directly from urban streets, a process that brings authentic, modern identity into his classical frameworks.

- Ornate Backgrounds: His vibrant, baroque-style floral patterns contrast sharply with the urban realism of his subjects, creating a visual tension that is both beautiful and thought-provoking.

- Scale and Presence: Like the Old Masters he references, Wiley often works on a monumental scale, giving his subjects a commanding and undeniable presence that fills the gallery space.

These components work together to create a visual language that is simultaneously reverent to art history and revolutionary in its message.

Actionable Takeaways

What can we learn from Kehinde Wiley’s strategy?

- Recast the Classics: Take a well-known story or image and change the "actors." This simple act can expose hidden biases and create a powerful new perspective on a familiar narrative.

- Blend High and Low: Combine classical, high-art aesthetics with contemporary, everyday elements (like street fashion). This fusion creates a dynamic tension that makes the work feel both timeless and urgently relevant.

- Empower the Overlooked: Use your creative work to give a platform to voices and faces that are often marginalized. Art can be a powerful tool for correcting historical imbalances in representation.

5. Zeng Fanzhi's The Last Supper (2001)

Moving from Western pop culture to Eastern political commentary, Zeng Fanzhi’s 2001 masterpiece offers a profound and unsettling vision of The Last Supper. The Chinese contemporary artist transplants Leonardo's iconic scene into the context of modern China, swapping Christ and his apostles for a group of Young Pioneers, identifiable by their red scarves, the symbol of the Communist Youth League.

The painting is massive and immediately confrontational. The disciples, all wearing identical, eerie masks, are engaged in a tense meal, their individuality erased. Judas is the only figure wearing a Western-style tie, a clear signifier of his betrayal through capitalist ambition. The work sold for a record-breaking $23.3 million in 2013, cementing its status as a pivotal piece of last supper modern art.

Analysis: Conformity and the Mask of Society

Zeng's reinterpretation is a powerful critique of the social and political pressures of his time. The masks, a recurring motif in his work, represent the loss of individual identity in a collectivist society. They are emotionless, hiding the true feelings of the figures and suggesting a world where authenticity is dangerous and conformity is the only safe path. The red scarves are not symbols of youthful innocence but of political indoctrination.

Strategic Insight: By using the structure of a revered religious painting to frame a political critique, Zeng elevates his commentary. He suggests that the betrayals and power dynamics of modern economic and political systems are as dramatic and consequential as the biblical narrative.

The familiar composition becomes a stage to explore the tensions between communism and burgeoning capitalism in China, making the viewer question who is loyal and who is the traitor in this new world order.

Actionable Takeaways

How can we apply Zeng Fanzhi's layered approach?

- Use Historical Frameworks: Repurpose a well-known historical or religious composition to give your modern commentary immediate weight and familiarity. This provides a shortcut for the audience to understand the underlying power dynamics.

- Symbolism is Key: Embed your message in powerful symbols. The masks, red scarves, and Western tie in Zeng’s work are not subtle; they are direct visual cues that carry immense cultural and political significance.

- Create Unsettling Ambiguity: The emotionless masks create a sense of unease. By hiding the figures' true intentions, you force the audience to project their own interpretations onto the scene, making the artwork more engaging and thought-provoking.

6. David LaChapelle's Jesus is My Homeboy: Last Supper

Known for his hyper-real and surreal fashion photography, David LaChapelle brings his signature high-gloss, pop-culture-infused aesthetic to Da Vinci's masterpiece. His photographic series, Jesus is My Homeboy, re-imagines biblical scenes in gritty, contemporary urban settings, and the Last Supper installment is a standout piece of this provocative collection.

LaChapelle replaces the solemn apostles of the Renaissance with a diverse, street-cast group of modern-day disciples. The setting is not a grand hall but a humble, almost bleak, urban environment. This striking contrast grounds the sacred event in a relatable, present-day reality, making the spiritual accessible to a generation raised on music videos and high-fashion magazines.

Analysis: Sanctity in the Streets

LaChapelle’s work thrives on the collision of the sacred and the secular, but his approach is distinctly different from Warhol's. Where Warhol used commercial logos to comment on mass consumption, LaChapelle uses fashion, realism, and urban culture to humanize religious figures. His Jesus is approachable, surrounded by a group that reflects the diversity and struggles of modern society.

Strategic Insight: By staging a sacred moment in a raw, contemporary setting with a diverse cast, LaChapelle strips away historical distance. He suggests that divinity and grace are not confined to ancient texts or museums but are present in the everyday lives of ordinary people.

This recontextualization is a powerful example of last supper modern art, demonstrating how photography can bridge the gap between historical religious iconography and contemporary social realities. It’s less a critique and more a vibrant, inclusive re-envisioning of faith.

Actionable Takeaways

What can we learn from LaChapelle's photographic reinterpretation?

- Modernize the Setting: Place a classic or historical theme into a completely modern and relatable context. This can make old ideas feel fresh, relevant, and immediately accessible to a new audience.

- Emphasize Human Connection: Focus on the characters and their interactions. LaChapelle’s composition highlights the camaraderie and intimacy of the group, making the scene feel less like a formal painting and more like a captured moment among friends.

- Use High-Contrast Aesthetics: Combine high-production, glossy photography with gritty, realistic subject matter. This tension between polished form and raw content creates a visually arresting image that demands attention and thought.

Modern Art Interpretations of The Last Supper: 6-Case Comparison

| Artwork / Artist | Implementation Complexity 🔄 | Resource Requirements ⚡ | Expected Outcomes 📊 | Ideal Use Cases 💡 | Key Advantages ⭐ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andy Warhol's The Last Supper (1986) | Moderate: silkscreen printing with multiple variations | High: large series, varied scales, studio resources | Strong cultural commentary on commercialization; multiple iterations enhance engagement | Exhibitions emphasizing Pop Art and mass culture | Bridges high art & pop culture; technical print mastery |

| Gerhard Richter's Abstract Last Supper | High: advanced squeegee painting abstraction | High: large canvases, complex technique | Creates contemplative, spiritual abstraction; appeals to broad audiences | Galleries focusing on abstract/spiritual art | Innovative technique; evokes spiritual essence |

| Susan Dorothea White's Feminist Last Supper | Moderate: realistic large-scale oil painting | Moderate: skilled portraiture & symbolic elements | Challenges gender norms; sparks conversations on inclusion | Feminist art shows; discussions on gender in religion | Combines tradition with social critique; inclusive focus |

| Kehinde Wiley's Last Supper (African American Subjects) | Moderate: photorealistic painting with ornate backgrounds | High: rich color use, detailed backgrounds | Highlights racial representation; visually impactful | Contemporary art addressing identity and power | Combines classical style with modern social commentary |

| Zeng Fanzhi's The Last Supper (2001) | High: expressive brushwork, distorted figures | High: large paintings with political themes | Powerful societal critique; emotional and cultural impact | Exhibitions on political art and modern China | Merges Eastern/Western traditions; strong visual impact |

| David LaChapelle's Jesus is My Homeboy | Moderate: high-end fashion photography production | High: models, locations, luxury styling | Makes religious themes accessible and modern; visually spectacular | Fashion & contemporary art intersections | Bridges sacred art with pop culture; technically masterful |

What These Modern Masterpieces Mean for Art Today

As we’ve journeyed through these stunning and provocative reinterpretations, one thing has become crystal clear: the narrative of the Last Supper is far from finished. The works of Warhol, Wiley, LaChapelle, and others show that this iconic scene is not a static relic preserved in amber. Instead, it’s a living, breathing canvas that contemporary artists use to explore our most pressing modern concerns. The enduring power of Leonardo's composition serves as a universal language, a familiar framework that allows artists to tell new, often challenging, stories about faith, identity, consumerism, and social justice.

The last supper modern art phenomenon is a powerful testament to the idea that art is a continuous conversation across centuries. Each piece we've examined, from Zeng Fanzhi's critique of Chinese society to Susan Dorothea White's bold feminist statement, doesn't just copy the original; it actively engages with it, questions it, and builds upon its legacy. This dialogue between past and present is what keeps art vibrant and relevant.

Key Takeaways from Modern Interpretations

So, what are the core lessons we can take away from these incredible examples?

- Familiarity Breeds Opportunity: By using a universally recognized image, artists can immediately connect with their audience and then subvert expectations to deliver a powerful message. The familiar structure becomes a Trojan horse for new ideas.

- Context is Everything: Shifting the setting, changing the figures' identities, or altering the style transforms the entire meaning of the scene. Kehinde Wiley’s placement of Black men in the sacred space and David LaChapelle’s urban setting prove that context dictates content.

- Art as Social Commentary: These works are more than just aesthetic exercises. They are sharp, incisive critiques of the world we live in. They challenge viewers to question who is included, who is excluded, and what values our modern "suppers" truly represent.

Putting These Insights into Action

For art enthusiasts, collectors, and creators, the lesson here is twofold. First, when viewing art, look for the conversation. Ask yourself: What historical or cultural symbol is the artist using? What new meaning are they creating by re-contextualizing it? This deepens your appreciation and connection to the work.

Second, for those who create or commission art, think about the power of shared symbols in your own life. Just as these artists used the Last Supper, consider how timeless themes can be used to tell your unique story. Whether it's capturing the enduring spirit of a beloved pet or the wild soul of a coastal landscape, art has the power to connect personal narratives to universal truths. By understanding the strategies behind last supper modern art, we learn to see the potential for profound storytelling in both the grand and the intimate moments of our lives.

At William Tucker Art, we believe every piece of art should tell a story. Just as modern masters reinvent timeless themes, William channels the vibrant energy of New Orleans and the natural world into custom pet portraits and wildlife art that feels both classic and contemporary. Discover how to tell your story through art at William Tucker Art.